NOT JUST BLING

Photo Doug Joyce | Cal Tech

07 May 2014

Though the architectural elite certainly don’t make a top priority of it, their work can sometimes contribute to good urban design. 'Good Urban Design' would be by definition a building or project that contributes to the City’s character and function as a whole, as opposed to simply acting as a bauble on display along the streets, for the purpose of adding gratuitous 'bling’ added to the surroundings. This rap on the elite designers, as broadcast as a universal truth by many in the urban design world, who cannot be convinced otherwise. These urbanists insist that modern building design does not now, never has, and never will contribute to great city building. The thought is that the great designers are inherently unwilling to participate in building 'urban fabric' in a meaningful way, especially if it undermines a theoretical premise, or the ’set of rules’ of their work is established on.

I would imagine that there must be pressure from the other side, too. The great ones will get dissed by their own contingent to avoid giving folks the wrong idea that they are paying too much attention to context, and not enough to the art and theory of their work. Yet by accident or design, the work of the elite actually does contribute to improving a city. It's nice when it happens.

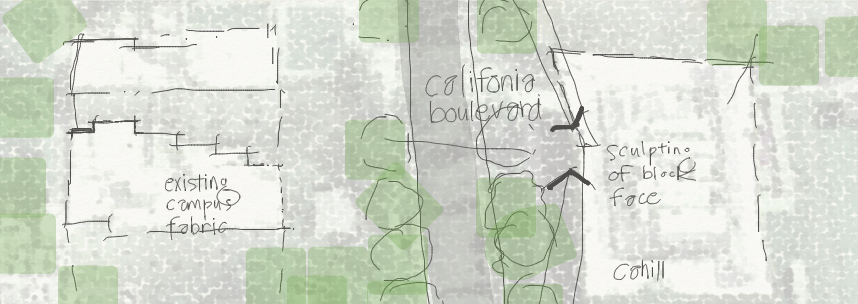

Here in Pasadena, Morphosis has pulled this off, on California Boulevard, on the CalTech campus.

CalTech is a place that is a veritable New Urbanist case study to clearly display the created calamities of modern architecture. After building a campus of great Spanish Colonial buildings, celebrated through Souther California, it was seen fit to construct a series of perfectly awful modern buildings, which over time have diminished its character and usefulness.

Morphosis comes in, and conceives the Cahill Center for Astrophysics, and it is a good building and good urban design. It's simply the best building that has been built on that campus in a number of decades, and greatly contributes to the processional experience along California Boulevard, the street that it faces. It also unifies the surrounding campus buildings, and surrounding pedestrian pathways.

The Morphosis trademark design features are in place. But the usual fractal surfacing and modeling is restrained in such a way so as to not interrupt the essential massing along the street. It's traced angular shapes dialog with the geometry of the surrounding trees. The block face provided by the structure gently gives way in the center, subtly in dialog with the surrounding buildings. The terra cotta hued rainscreen panels, the predominantly expressed exterior finish, relate with the color of the barrel tile roofing of the more traditional buildings near by. The glazing at the front of the building gives just enough of a clue as to what is going on inside, that is not a dark mass against the street edge. There are key locations where one can glance at or gain access to the grass area defined at the back of the building; they invite you through the building, and into the campus enclosed outdoor space.

In the Morphosis cannon, the Cahill Center may be considered to be a secondary work. It's been up and going for almost 5 years, and after a brief splash when it opened, the critics have left it alone. Thom Mayne (the Morphosis head himself) considers the building to be "probably the most conservative" (1) work he's done. So he's a bit dismissive of the Cahill, though seemingly still proud.

There seems to be a necessity for the great artists and architects to pursue their theories, to come up with their forms, and their manipulations of light and texture; their singular ideas. We're all enlightened and inspired by these inventions. Yet many times they only provide one aspect, one dimension, one (sometimes participating unwilling) contribution to the greater construction of the whole city. I would encourage them to make a more daring and complete vision, one that incorporates surrounding elements and considers all that has been put in place prior to the creation of their new work. Not just on a theoretical level, but in the most practical of ways. Not just in a static, or just in appreciating the local dynamics of form, but also what happen as one moves up to, and then passes by this creation, and how does that affect the experience of the individual making the progression. And not just from the aspect of what has already happened in this environment, but what will happen in the future.

1 Interview of Thom Mayne by Christopher Hawthorne of the Los Angeles Times, 16 February 2009